This is how expensive the ban on gas and oil heating systems will be

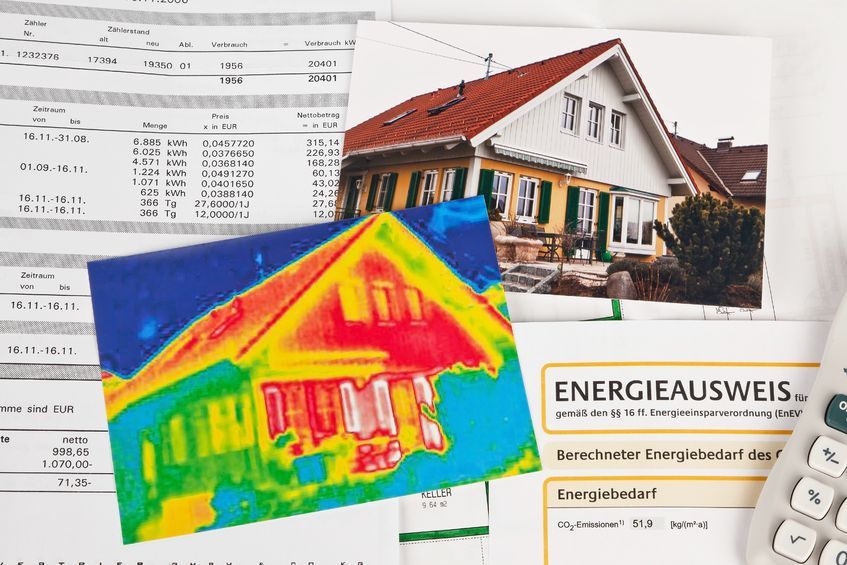

From 2030 onwards, heating systems in new residential buildings will no longer be permitted to use fossil fuels. That's the plan. But many technical questions remain unanswered – and the costs for residents are enormous.

The energy transition is a top priority for the German government. Greenhouse gas emissions from industry, road transport, and buildings are to be reduced as quickly as possible. However, a crucial question in the shift to renewable energies is: Who will move forward, and how quickly?

A recent draft of the government's 2050 climate action plan sets out key goals for the coming decades and provides a clear answer: Homeowners should be the first to completely abandon fossil fuels. Only then will cars and commercial enterprises follow.

From 2030 onwards, gas or oil heating systems will no longer be permitted in newly constructed residential buildings, from apartment buildings to single-family homes on the outskirts of cities – that's the plan. The climate protection document, which is available to the newspaper "Die Welt," states: "By 2030 at the latest, the installation of new heating systems based on the combustion of fossil fuels must be prohibited."

In 13 years, building owners will face a turning point

While the climate protection plan allows considerable leeway for the switch to renewable energy in cars and commercial buildings, building owners must expect a paradigm shift in just over 13 years. "For new buildings to be constructed by 2030, this means that the energy efficiency requirements for residential buildings, based on final energy consumption, must be further developed to a value below 30 kilowatt-hours per square meter," the regulations state. This value is significantly lower than the already stringent new building requirements of the Energy Saving Ordinance (EnEV).

At first glance, a complete ban on oil and gas heating systems might seem to have a positive impact on the climate and on homeowners' wallets. However, because the necessary infrastructure for switching to renewable energy is lacking, technical issues, especially in multi-family buildings, remain unresolved, and alternative heating technologies are still in their infancy in many areas, the government plan ultimately leads primarily to increased costs for homeowners and apartment owners.

Electricity prices and consumption are likely to rise further. And even greenhouse gas emissions could be significantly higher than expected. This is because increasing amounts of electricity are needed for heating, and a good portion of that is likely to be generated by coal-fired power plants during the winter months.

The rattling fans are often louder than you'd expect

From Corinna Kodim's point of view, home builders will have few alternatives when choosing a heating system from 2030 onwards: "Many private builders will probably have to resort to a heat pump, even though they know that the running costs can be very high due to the price of electricity," says the speaker for energy, environment and technology at the homeowners' association Haus & Grund.

For reference: A kilowatt-hour of natural gas currently costs 6.23 cents, while a kilowatt-hour of electricity for a heat pump costs 23 cents. To assess the cost of a heat pump, there's the seasonal performance factor (SPF) – a factor that, simply put, describes how many units of heat energy can be generated from one unit of electricity. An SPF of three essentially means a tripling of the output: To obtain one kilowatt-hour of heat energy, the pump requires electricity worth 7.66 cents.

At first glance, this seems just as inexpensive as gas heating. However, the calculation is highly theoretical. Heat pumps rarely achieve the performance figures promised in the brochure. This is because the calculation of the seasonal performance factor (SPF) is based on consumer behavior that rarely occurs in the real world. Experts observe that even heating the living room to 24 degrees Celsius instead of the target temperature of 22 degrees in winter is enough to trigger the dreaded emergency heating element. Just like with an immersion heater, the required hot water is then produced directly using electricity, and costs skyrocket.

The German Property Owners' Association (Haus & Grund) is aware of another problem: "There are often issues with noise levels and disputes with neighbors," says Kodim. "The specifications on paper only provide information about the sound pressure level under standard conditions, not what actually reaches the neighbors." At night, the permissible noise level for residential areas is 35 dB(A). "This value must not be exceeded at the nearest window." However, a growing number of legal disputes suggests that the rattling fans in these units are often louder than expected.

This certainly applies to the widespread and relatively inexpensive air-source heat pumps. An alternative would be heat pumps that utilize geothermal energy via deep drilling. However, expert Kodim also points out a caveat: "Geothermal heat pumps are not permitted everywhere or technically feasible." Furthermore, the installation costs are very high due to the deep drilling required.

Do not drop out of funding

What is a costly decision for the small homeowner is even more so for large developers: "Air source heat pumps are only suitable up to a certain building size," says Ingrid Vogler, consultant for energy, technology and standardization at the Association of Housing Companies. "This technology is generally not an option for larger apartment buildings in inner-city areas." Deep drilling for geothermal heat pumps is rare in urban areas, as is the use of wastewater heat.

Combined heat and power plants fueled by biogas have become uneconomical since biogas subsidies ended. And for the exclusive use of solar thermal energy, i.e., hot water generated by solar power, affordable storage technologies for winter are still lacking. The bottom line is this: unless a dense district heating network happens to exist locally, there is currently practically no economically viable heating alternative for newly built standard rental apartments in the city center for the future, starting in 2030.

The potential drawbacks of electric heating, at least with today's technology, are described by Kodim, an expert from the German Property Owners' Association: "With heat pumps, there's a problem with hot water preparation. To keep the hot water storage tank free of Legionella, the water must be maintained at a temperature of 60 degrees Celsius." A modern underfloor heating system, on the other hand, requires lower flow temperatures. Operating both heating systems simultaneously often leads to poor efficiency, and there's no government funding available for this.

To avoid losing their eligibility for subsidies, some providers are now even suggesting the installation of two heat pumps: one for heating, which requires a consistently low flow temperature and, at least on paper, achieves the required annual performance factor. "And one for heating domestic hot water and service water, which then consumes significantly more electricity," says Kodim.

A massive expansion of the electricity infrastructure is needed

But the unpredictable heating costs for consumers aren't the only issue. To provide enough electricity for the many new electric heating systems, a massive expansion of the electricity infrastructure is needed. And as the past has shown, these costs will ultimately be passed on to private electricity customers. The "Future Natural Gas" initiative states: "The costs for electrifying the heating market amount to approximately 2 trillion euros. That would correspond to about 50,000 euros per household."

That "Future Natural Gas" is targeting electricity-based heat generation is hardly surprising. However, the initiative also champions the development of a completely different heating technology using renewable energies: "Power to Gas." Here, green electricity is used for the electrolysis of water – producing hydrogen and, in a further step, methane gas. Converted into this form, energy could be stored and transported using the existing infrastructure. Timo Leukefeld, energy consultant and expert in eco-heated buildings, says: "I believe it is significantly more effective to make the gas network greener than the electricity grid."

The ban on gas and oil heating systems from 2030 onwards is initially intended to apply only to new buildings. However, homeowners and apartment owners with existing properties can also expect stricter requirements. The Climate Action Plan 2050 states: "To achieve a climate-neutral building stock in the long term, significantly more and significantly faster investment in the energy optimization of existing buildings is necessary. By 2030 at the latest, the energy efficiency after renovation may only exceed the new building standard by 40 percent in exceptional cases."

Source: Die Welt